I was looking at my database logs the other day—mostly because the dev server was choking on a simple query—and I saw it. The classic wall of text. You know the one. I asked for a list of 20 users, and my application decided that was the perfect opportunity to fire off 21 separate database queries. One for the users, and then twenty more to fetch their profiles individually.

The N+1 problem is like the cockroach of GraphQL development. You think you’ve squashed it, but then you add a new relation, and suddenly your latency spikes. If you’re using NestJS with MikroORM, fixing this isn’t exactly “out of the box” behavior, despite what some tutorials might imply. I’ve spent more hours than I care to admit trying to get dependency injection to play nice with Dataloaders.

So, let’s fix this. Properly. Whether you’re running Apollo or Mercurius (I’ve switched between both recently), the logic remains pretty much the same. We need to batch those requests before your DBA comes looking for you.

The “Oh No” Moment

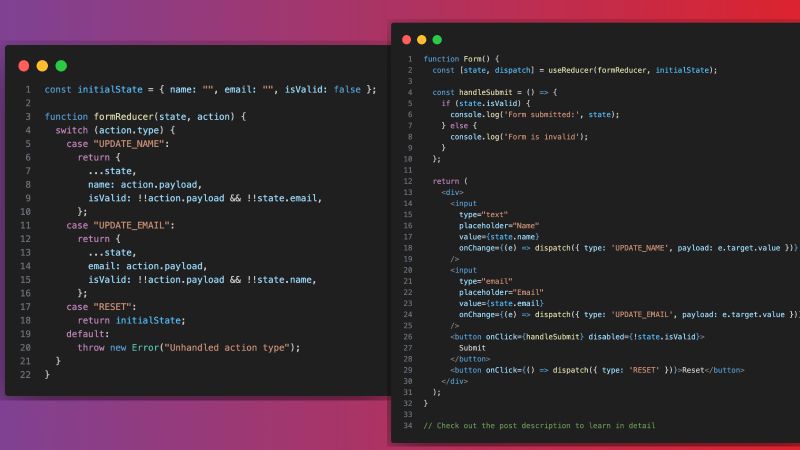

Here’s what usually happens. You write a clean, innocent resolver. It looks fine in code review.

@ResolveField()

async posts(@Parent() author: Author) {

// This looks harmless, right?

// But if you fetch 50 authors, this runs 50 times.

return this.postsRepository.find({ author: author.id });

}This is the trap. GraphQL executes resolvers for each field independently. It has no idea that you’re about to ask for the exact same data for the next item in the list. It just blindly executes. If you have a list of 100 items, you just hammered your database 101 times.

Enter Dataloader (The Batcher)

The standard fix is the dataloader library. Conceptually, it’s simple: instead of executing a query immediately, you tell the loader “I need data for ID 1.” The loader says “Cool, hold on.” Then the next resolver asks for ID 2. The loader says “Got it.”

At the end of the event loop tick (or strictly speaking, next tick), the loader looks at its queue, sees a bunch of IDs, and fires one query: SELECT * FROM posts WHERE author_id IN (1, 2, ...).

But here’s where it gets messy in NestJS: Scope.

Dataloaders must be request-scoped. You cannot share a dataloader instance across requests, or you’ll end up caching data for User A and serving it to User B. That’s a security nightmare waiting to happen. But NestJS singletons are the default. See the conflict?

The MikroORM Setup

I prefer creating a dedicated factory for my loaders. It keeps the logic out of the resolvers and makes testing way less annoying. Since we’re using MikroORM, we can leverage its Collection handling, but honestly, I prefer raw ID matching for speed here.

First, let’s build a generic loader factory. I’m keeping this TypeScript-heavy because, well, types save lives.

import DataLoader from 'dataloader';

import { Injectable, Scope } from '@nestjs/common';

import { EntityManager } from '@mikro-orm/core';

import { Post } from './entities/post.entity';

// We make this REQUEST scoped so a new instance is created for every incoming HTTP request

@Injectable({ scope: Scope.REQUEST })

export class DataLoaderService {

constructor(private readonly em: EntityManager) {}

// The actual loader instance

public readonly postsByAuthorLoader = new DataLoader<string, Post[]>(

async (authorIds: readonly string[]) => {

// 1. Fetch all posts for these authors in ONE query

const posts = await this.em.find(Post, {

author: { $in: authorIds },

});

// 2. Group the results by author ID

// This part is crucial. The loader expects the array of results

// to match the exact order of the input keys (authorIds).

const postsMap = new Map<string, Post[]>();

posts.forEach(post => {

const authorId = post.author.id;

if (!postsMap.has(authorId)) {

postsMap.set(authorId, []);

}

postsMap.get(authorId)?.push(post);

});

// 3. Map back to the original array of keys

return authorIds.map(id => postsMap.get(id) || []);

}

);

}Wait, did you catch that mapping logic at the end? That’s where I screwed up the first time I implemented this. Dataloader requires the returned array to be the exact same length and in the exact same order as the input keys. If you just return the results from the DB, and one author has no posts, your array will be shorter, and everything will be misaligned. Chaos ensues.

Wiring it into the Resolver

Now that we have a service that generates our loader, we need to inject it. Since we marked the service as Scope.REQUEST, NestJS handles the lifecycle for us. We don’t need to manually attach it to the GraphQL context context (though that is another valid strategy if you want to keep your resolvers pure singletons).

I usually just inject the service directly into the resolver. It forces the resolver to be request-scoped too, which has a tiny performance hit, but honestly? Unless you’re serving Twitter-scale traffic, the overhead of request-scoped resolvers is negligible compared to the latency of 50 extra database calls.

@Resolver(() => Author)

export class AuthorResolver {

constructor(

private readonly dataLoaderService: DataLoaderService

) {}

@ResolveField(() => [Post])

async posts(@Parent() author: Author) {

// Instead of direct DB access:

// return this.postRepo.find({ author: author.id });

// We use the loader:

return this.dataLoaderService.postsByAuthorLoader.load(author.id);

}

}Alternative: The Context Approach

If you are strict about keeping your resolvers as Singletons (which, fair play, is technically more performant), you can’t inject a request-scoped service into them. In that case, you pass the loader through the GraphQL context.

In your app.module.ts (or wherever you configure GraphQL):

GraphQLModule.forRootAsync<ApolloDriverConfig>({

driver: ApolloDriver,

useFactory: (dataLoaderService: DataLoaderService) => ({

autoSchemaFile: true,

// Attach loaders to context

context: () => ({

loaders: dataLoaderService.createLoaders() // You'd need to refactor the service slightly

}),

}),

// This is the trick to inject request-scoped providers into the context factory

inject: [DataLoaderService],

}),I find the Context approach a bit cleaner architecturally because it separates “fetching mechanics” from “business logic,” but it does make the types in your resolvers a bit messier since ctx.loaders is often typed as any unless you’re rigorous with your interfaces.

Why MikroORM Makes This Tricky

MikroORM has an Identity Map. This is great for performance usually, but when batching, you need to be careful. If you load entities in a batch, make sure your EntityManager fork is correct. If you use the request-scoped service approach I showed first, NestJS automatically gives you the request-scoped EntityManager (assuming you set up MikroOrmModule correctly).

If you try to do this globally or with a singleton EntityManager, you’ll run into issues where entities from previous requests hang around. I’ve been burned by that. Seeing data from “User A” appear in “User B’s” request is the kind of bug that makes you want to change careers and become a woodworker.

Final Thoughts

Solving N+1 isn’t just about making the graph green on your monitoring dashboard. It’s about predictability. Without Dataloaders, the cost of a query is unpredictable—it depends on the data size. With Dataloaders, the cost is constant: one query for the list, one query for the relations.

Is it more boilerplate? Yeah, absolutely. Writing a loader for every relationship is tedious. But the first time your app survives a traffic spike because your database wasn’t getting hit with 5,000 queries per second, you’ll be glad you took the time.