It happened again. I honestly thought we were done with this specific flavor of security headache, but apparently, 2025 had one last curveball for us. If you’ve been online this week, you’ve seen the panic about expr-eval. Another remote code execution (RCE) flaw in a library that exists solely to do math. Math.

I’ve been writing JavaScript for fifteen years. In that time, I’ve seen eval() go from “standard practice” to “never do this” to “well, maybe if you use a library it’s okay.”

Spoiler: It’s not okay.

The recent vulnerability in expr-eval isn’t just a bug; it’s a symptom of our obsession with convenience. We want to let users type price * quantity into a text box and have it magically work, but we forget that under the hood, we’re handing them the keys to the engine.

The Illusion of Safety

Here’s the thing. Most developers know eval() is bad. So we grab a library. We think, “Hey, this library parses the string, it doesn’t just run it, so it’s safe.”

I fell for this trap a few years ago on a dashboard project. We needed user-defined metrics. I grabbed a popular expression parser, plugged it in, and went to lunch. It worked great until a penetration tester showed me how she could dump our entire environment variables list just by typing a weird math formula.

The problem is usually prototype access. Even if a library blocks eval, if it allows access to object properties, an attacker can climb up the prototype chain.

Let’s look at a typical “innocent” setup. You might have an API that returns a formula, and you want to run it on the client side.

// The "Safe" Approach (That isn't actually safe)

async function calculateUserMetric(userId) {

try {

// Fetch the user's custom formula from our API

const response = await fetch(/api/user/${userId}/formula);

const data = await response.json();

// data.formula might be: "revenue - cost"

// But what if it's malicious?

const context = {

revenue: 1000,

cost: 400,

meta: { version: '1.0' }

};

// Hypothetical unsafe usage of a parser

// This looks clean, but if the library has an RCE flaw...

const result = unsafeLibrary.evaluate(data.formula, context);

updateDom(result);

} catch (error) {

console.error("Calculation failed", error);

}

}

function updateDom(value) {

const display = document.getElementById('metric-display');

if (display) {

display.innerText = $${value};

}

}Looks standard, right? You fetch data, you run logic, you update the DOM. But the devil is in that evaluate function.

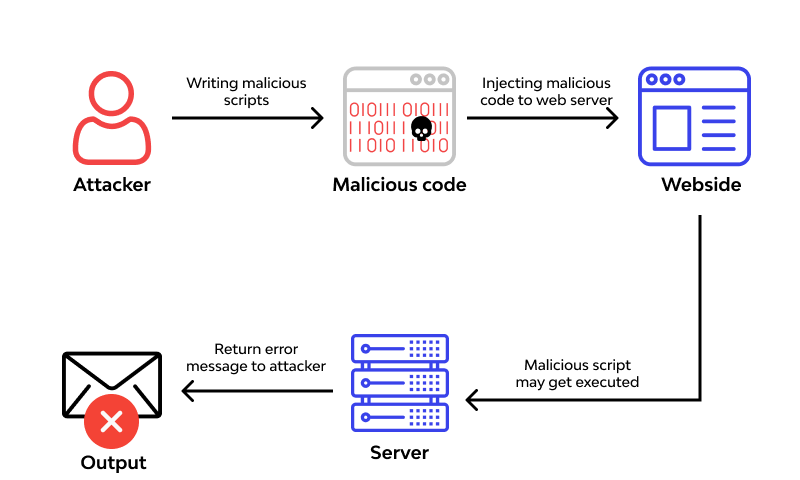

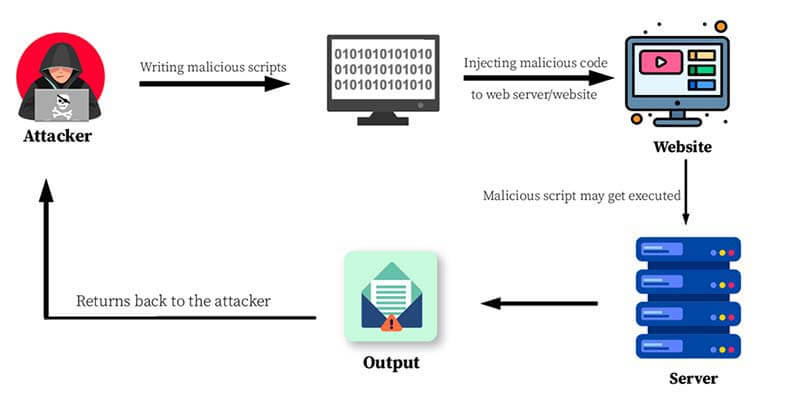

How the Break Happens

The recent flaw exploits the fact that in JavaScript, everything is an object. If the expression parser allows property access (like meta.version), clever attackers can access the constructor.

Once you have the constructor of a basic object, you can get the Function constructor. And once you have the Function constructor, you can create arbitrary functions. It’s game over.

Here is what a payload looks like when it hits your “math” library. I’m simplifying, but the logic holds:

// The payload hidden in the "formula" string

// Instead of "revenue - cost", the attacker sends:

const maliciousFormula =

constructor

.constructor("return process")()

.mainModule.require("child_process")

.execSync("rm -rf /")

;

// If the library evaluates property access loosely:

// 1. Accesses 'constructor' of the context object

// 2. Accesses 'constructor' of that (which is the Function constructor)

// 3. Creates a new function that returns the global 'process' object

// 4. Executes it to get 'process'

// 5. Requires 'child_process' and runs shell commands

;</code></pre>

<!-- /wp:code -->

<!-- wp:paragraph -->

<p>This is why the <code>expr-eval</code> news from earlier this week scared me. It’s not just about one library; it’s about the architectural decision to allow dynamic execution at all.</p>

<!-- /wp:paragraph -->

<!-- wp:heading -->

<h2>A Better Way: The Sanitized Sandbox</h2>

<!-- /wp:heading -->

<!-- wp:paragraph -->

<p>So, what do we do? Stop using math? No.</p>

<!-- /wp:paragraph -->

<!-- wp:paragraph -->

<p>I stopped using general-purpose expression evaluators for critical paths about two years ago. Now, I write restricted parsers or use libraries that don't support property access by default. If I need to allow users to do math, I explicitly whitelist the variables they can touch.</p>

<!-- /wp:paragraph -->

<!-- wp:paragraph -->

<p>Here is a safer, albeit more manual, way to handle this using a <code>Function</code> generator with a null prototype context. It's still risky if you aren't careful, but it's miles better than a raw library import because you control the scope.</p>

<!-- /wp:paragraph -->

<!-- wp:code {"language":"javascript"} -->

<pre class="wp-block-code"><code>function safeEvaluate(formula, variables) {

// 1. Sanitize the input

// Allow only numbers, operators, and known variable names

// This Regex is aggressive - adjust as needed

const allowedPattern = /^[0-9+\-*/().\s\w]+$/;

if (!allowedPattern.test(formula)) {

throw new Error("Invalid characters in formula");

}

// 2. Create a function with a restricted scope

// We use the Function constructor, but we wrap it carefully

const keys = Object.keys(variables);

const values = Object.values(variables);

// "use strict" helps, but isn't a silver bullet

const func = new Function(...keys, "use strict"; return (${formula});`);

// 3. Execute

return func(...values);

}

// Usage

const userVars = {

revenue: 1000,

cost: 500

};

try {

// This works

console.log(safeEvaluate("revenue - cost", userVars)); // 500

// This throws immediately because of the regex check

console.log(safeEvaluate("constructor.constructor...", userVars));

} catch (e) {

console.log("Attack blocked:", e.message);

}Is this perfect? No. The regex is brittle. If you miss one edge case, you’re vulnerable again. But it forces you to think about allow-listing rather than block-listing.

The Karma of Convenience

We keep hitting these issues because we want JavaScript to be something it isn’t. We want it to be a secure sandbox for user logic, but the language is designed to be dynamic and introspective. It wants to let you access the constructor. It wants to let you modify the prototype.

When you fight the language, the language eventually wins.

If you are using expr-eval or similar libraries in your stack right now, go check your versions. Patch it. But don’t stop there. Look at where you are using it.

Do you really need to evaluate that string on the server? Can you do it on the client where the impact is limited to that user’s browser? Or better yet, can you pre-calculate it?

I spent yesterday auditing a client’s codebase because of this news. I found three instances of eval() hidden in legacy utility files. Three. In 2025.

We have to do better.