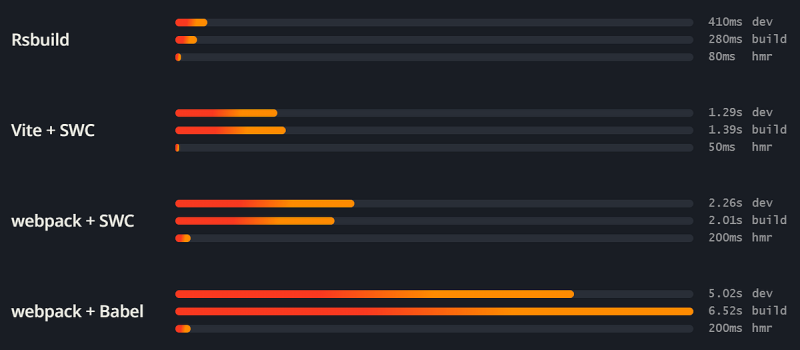

I remember exactly where I was when the “Turbopack is 10x faster than Vite” chart dropped a couple of years ago. Twitter was on fire. You had the Vercel camp posting rocket emojis, and you had Evan You politely (but firmly) dissecting the benchmarks. It was the kind of framework drama that makes web development feel more like reality TV than engineering.

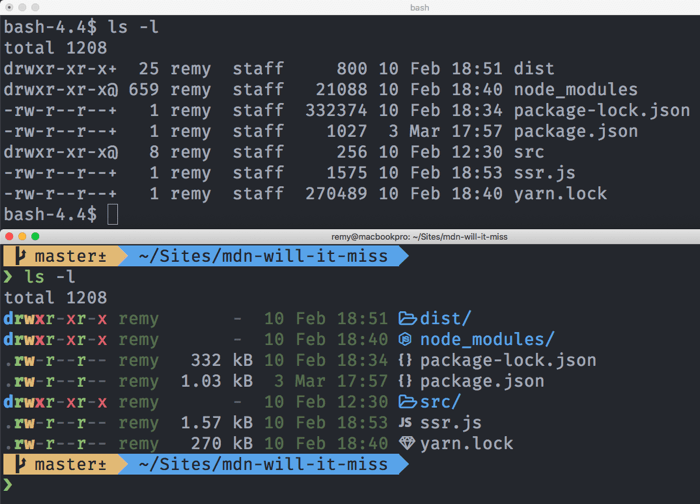

Fast forward to now. It’s late 2025. The dust has settled. And I’m sitting here staring at my terminal, watching a production build for a massive Next.js enterprise app.

Is it fast? Yeah. It’s fast.

Do I care about the “10x” claim anymore? Not even a little bit.

Here’s the thing about speed benchmarks: they exist in a vacuum. They measure cold starts of 50,000 generated components that do absolutely nothing. But your app isn’t a “Hello World” multiplied by 50k. It’s a messy pile of circular dependencies, heavy third-party libraries, and questionable architectural decisions you made three months ago at 2 AM.

The “Lazy” Architecture: Why It Actually Feels Faster

The real reason Turbopack feels snappy isn’t just because it’s written in Rust. It’s the architecture. Unlike Webpack, which tried to bundle the universe before serving your localhost, Turbopack (and Vite, to be fair) embraces laziness. But they do it differently.

Vite serves source files over native ESM. The browser does the heavy lifting of requesting imports. Turbopack, on the other hand, bundles on demand, but only what’s necessary for the current page.

I ran into a scenario last week where this distinction mattered. I was working on a dashboard with about 40 heavy data-viz components. In my old Webpack setup, changing a utility function shared by all of them would trigger a rebuild that gave me enough time to go make coffee. Literally.

With Turbopack, the HMR (Hot Module Replacement) updates are sub-100ms. It keeps me in the flow. But here is the catch: Vite is also sub-100ms for that same change. Once you get below a certain threshold, “faster” stops being perceptible to the human brain.

Here is a quick example of the kind of “heavy” component structure that usually chokes older bundlers, but flies now:

// DashboardWidget.jsx

import { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

import { heavyCalculation } from '../utils/math-stuff';

import DynamicChart from './DynamicChart'; // Lazy loaded

export default function DashboardWidget({ dataId }) {

const [metrics, setMetrics] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

// Simulating a heavy data crunch that might lock up the main thread

// if the bundler injects too much overhead code

const processData = async () => {

console.time('processing');

const result = await heavyCalculation(dataId);

console.timeEnd('processing');

setMetrics(result);

};

processData();

}, [dataId]);

if (!metrics) return <div className="animate-pulse h-64 bg-gray-100 rounded" />;

return (

<div className="p-4 border rounded shadow-sm">

<h3>Widget {dataId}</h3>

<DynamicChart data={metrics} />

</div>

);

}When you edit that heavyCalculation utility, Turbopack identifies the dependency graph instantly. It knows exactly which route segments are active and only recompiles the “path” to the browser. It doesn’t touch the 39 other widgets you aren’t looking at.

The Ecosystem Gap is Still Real

This is where I get annoyed. Speed is great, but compatibility is what lets me sleep at night. Vite has an absolutely massive plugin ecosystem. If there is a weird file format or a legacy tool you need to support, someone has written a Vite plugin for it.

Turbopack? It’s better than it was in 2023, for sure. But I still hit walls. Just the other day I was trying to migrate a legacy project that used some obscure Babel macros. In Vite, I just dropped in a plugin. In Turbopack, I had to rethink the build pipeline because it doesn’t support the full Webpack loader API 1:1, and it doesn’t use Vite plugins.

If you are staying strictly within the “Vercel / Next.js” happy path, it’s magic. You turn it on in your config and forget about it:

// next.config.js

/** @type {import('next').NextConfig} */

const nextConfig = {

// We used to have to explicitly enable this, now it's mostly default behavior

// but for specific granular control or experimental features:

experimental: {

// If you're still tweaking internal turbopack settings

turbo: {

rules: {

// Mapping non-standard files to loaders

'*.svg': ['@svgr/webpack'],

},

resolveAlias: {

underscore: 'lodash',

},

},

},

};

module.exports = nextConfig;But step outside that garden? You might be writing your own Rust bindings if you aren’t careful. Okay, that’s an exaggeration, but you get my point.

Server Components: The Real Battlefield

The argument about “Vite vs Turbopack” misses the point of where web dev is actually going. It’s all about Server Components now. The bundler isn’t just bundling client assets anymore; it’s orchestrating a complex dance between server-side logic and client-side hydration.

This is where Turbopack starts to justify its existence. Because it’s tightly coupled with the Next.js architecture, it handles the RSC (React Server Components) payload splitting incredibly well. Debugging async server components used to be a nightmare of opaque errors. Now, the stack traces actually make sense.

Check out this pattern. In a traditional bundler, mixing server-only logic with client interactions often led to leakage—server code ending up in the client bundle. Turbopack seems much stricter (and smarter) about tree-shaking this stuff:

// app/actions.js

'use server';

import db from '@/lib/db';

// This function NEVER leaks to the client bundle

export async function submitForm(formData) {

const rawData = Object.fromEntries(formData);

// Direct DB access - safe here

await db.users.create({

data: rawData

});

return { success: true };

}

// app/form-client.jsx

'use client';

import { submitForm } from './actions';

import { useState } from 'react';

export default function SignupForm() {

const [status, setStatus] = useState('idle');

return (

<form action={async (formData) => {

setStatus('submitting');

await submitForm(formData); // Turbopack handles this RPC call bridge

setStatus('done');

}}>

<input name="email" type="email" required />

<button disabled={status === 'submitting'}>

{status === 'submitting' ? 'Saving...' : 'Sign Up'}

</button>

</form>

);

}When I look at the build output for this, the client bundle is tiny. It just contains the form logic and a reference ID for the server action. Vite implements this too (via frameworks like Remix or Nuxt), but the integration in the Next.js/Turbopack stack feels incredibly cohesive right now.

So, Who Wins?

If you asked me two years ago, I would have said Vite wins by default because it’s open, plugin-rich, and “fast enough.”

Today? It depends on your zip code.

If you live in Next.js land, Turbopack is the winner. Not because it’s 10x faster—though the speed is nice—but because it understands the framework’s weird, complex hybrid architecture better than anything else. It fails less often on edge cases involving Server Actions and streaming.

But for literally everything else—Vue, Svelte, vanilla React SPAs, backend-heavy apps with a light frontend—Vite is still the king. It’s the standard. I don’t see that changing anytime soon.

My advice? Stop obsessing over the benchmarks. Unless your build takes 20 minutes, the bottleneck isn’t the bundler. It’s probably your TypeScript type-checking or your CI pipeline installing dependencies. Fix that first.