Introduction: The Quest for Infinite Detail

The landscape of web graphics is undergoing a seismic shift. For over a decade, Three.js News has been dominated by the constraints of WebGL: draw call limits, memory bottlenecks, and the delicate balancing act of polygon counts. However, inspired by native engine advancements like Unreal Engine’s Nanite, the web graphics community is now actively exploring virtualized geometry. This technique promises a future where artists can import movie-quality assets directly into the browser without manual retopology or baking normal maps.

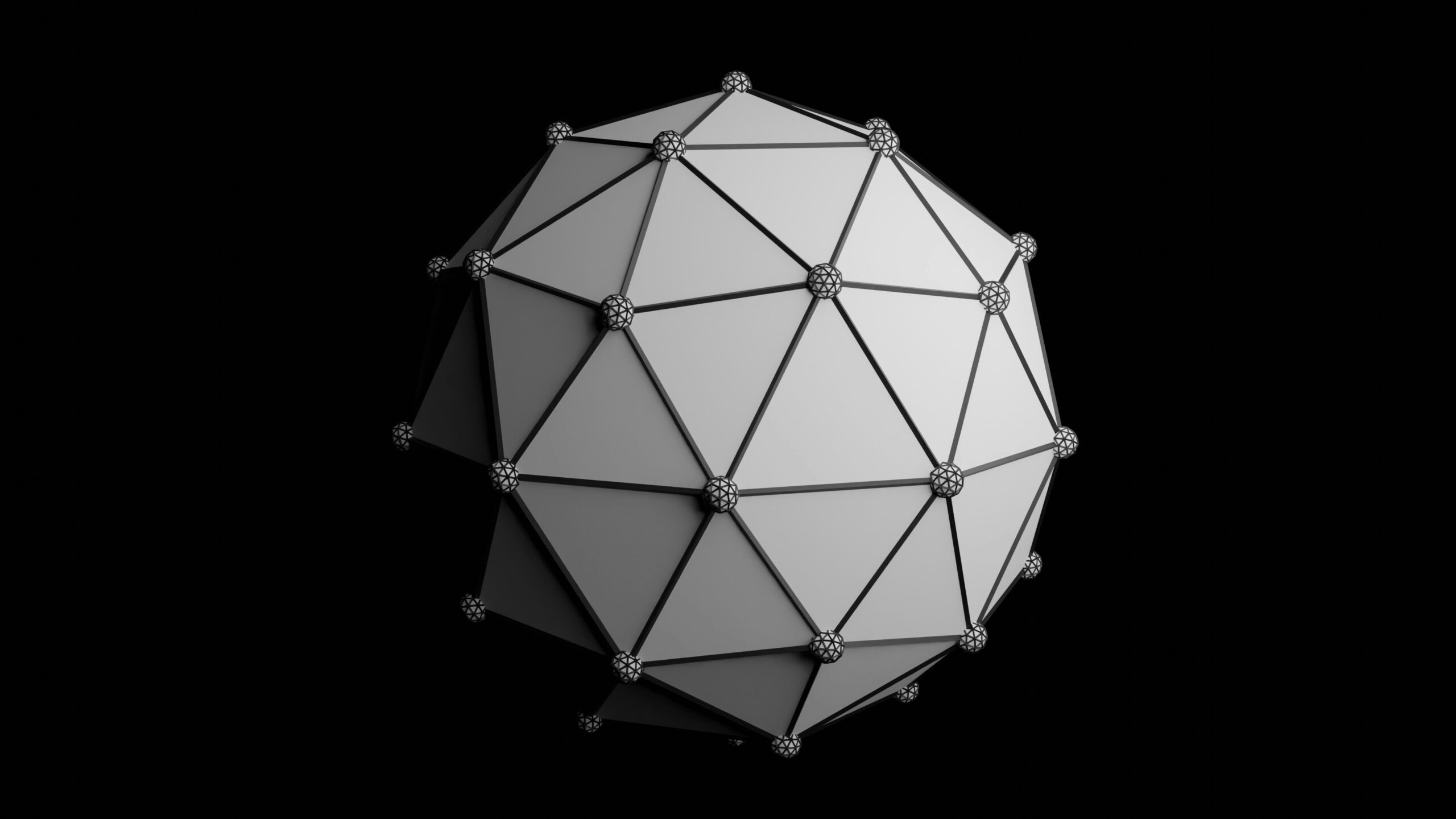

Virtualized geometry fundamentally changes how we render 3D scenes. Instead of rendering whole objects, the engine breaks geometry down into “meshlets” or “clusters”—small groups of triangles that can be streamed, culled, and scaled independently. This allows for continuous Level of Detail (LOD) that is imperceptible to the user, maintaining pixel-perfect density regardless of camera distance.

While frameworks covered in React News, Vue.js News, and Angular News focus on DOM efficiency, the 3D web is focused on GPU throughput. Whether you are integrating 3D into a dashboard covered in Next.js News or a desktop application highlighted in Electron News, understanding the mechanics of GPU-driven rendering is essential for the next generation of immersive web experiences. In this article, we will dissect the technical architecture required to bring virtualized geometry to Three.js.

Section 1: The Core Concept—Meshlets and Cluster Culling

The traditional rendering pipeline in Three.js relies on frustum culling at the object level. If a mesh’s bounding box is within the camera’s view, the GPU processes every vertex in that mesh. For a high-fidelity statue with 2 million triangles, this is inefficient if the object is far away or partially occluded.

To implement a virtualized geometry system, we must abandon the concept of the “Mesh” as the atomic unit of rendering. Instead, we preprocess geometry into Meshlets. A meshlet is a small cluster of triangles (usually 64 to 128) that shares a local bounding sphere. This granularity allows the GPU to decide exactly which parts of an object to draw.

Preprocessing Geometry

Before we can render, we need to split our geometry. While robust implementations use C++ tools or WebAssembly (Wasm) libraries like meshoptimizer, we can visualize the logic in JavaScript. The goal is to traverse the index buffer and group triangles based on spatial locality.

import * as THREE from 'three';

/**

* A conceptual simplified function to split geometry into chunks (Meshlets).

* In production, use meshoptimizer or a WASM module for performance.

*/

function generateMeshlets(geometry, maxVertices = 64, maxTriangles = 124) {

const positions = geometry.attributes.position.array;

const indices = geometry.index ? geometry.index.array : null;

if (!indices) return; // Only indexed geometry is supported for this technique

const meshlets = [];

// Conceptual iteration: In reality, use K-Means or spatial hashing

// to group triangles that are close to each other.

let currentMeshlet = {

vertices: [],

indices: [],

boundingSphere: new THREE.Sphere()

};

for (let i = 0; i < indices.length; i += 3) {

// Logic to add triangle (i, i+1, i+2) to currentMeshlet

// If currentMeshlet exceeds maxVertices or maxTriangles:

// 1. Compute bounding sphere for the meshlet

// 2. Push to meshlets array

// 3. Start new meshlet

}

return meshlets;

}

// Usage within a Three.js scene setup

const heavyMesh = new THREE.TorusKnotGeometry(10, 3, 300, 50);

// Ideally, this happens in a Web Worker or build step (Vite/Webpack)

const meshletData = generateMeshlets(heavyMesh);

console.log(`Generated ${meshletData.length} meshlets for processing.`);This preprocessing step is crucial. By organizing data this way, we prepare the geometry for GPU-driven culling. In the context of TypeScript News, defining strict interfaces for your Meshlet structures is highly recommended to manage the complexity of the binary data streams required for this technique.

Section 2: Implementation—GPU-Driven Rendering

Once we have meshlets, we cannot simply create thousands of THREE.Mesh objects; the CPU overhead (draw call overhead) would destroy performance. This is a common topic in Babylon.js News and PixiJS News as well: minimizing CPU-GPU communication is key.

To render thousands of meshlets efficiently in Three.js, we leverage THREE.InstancedMesh or, for more advanced control, THREE.BatchedMesh (a recent addition to the core). However, true virtualized geometry requires moving the culling logic to the shader. We use a technique called "Compute Culling" (or vertex shader culling in WebGL 2.0).

Anonymous AI robot with hidden face - Why Agentic AI Is the Next Big Thing in AI Evolution

The Culling Shader

We can encode the bounding sphere of each meshlet into a Data Texture or an Instanced Attribute. The vertex shader then checks if the meshlet is within the camera frustum. If it is not, we collapse the geometry to a degenerate state (setting position to NaN or 0), effectively preventing the rasterizer from processing pixels.

// Custom ShaderMaterial for Meshlet Rendering

const meshletMaterial = new THREE.ShaderMaterial({

vertexShader: `

attribute vec3 instancePosition; // Center of the meshlet

attribute float instanceRadius; // Bounding radius

varying vec2 vUv;

void main() {

vUv = uv;

// 1. Transform meshlet center to View Space

vec4 viewPos = modelViewMatrix * vec4(instancePosition, 1.0);

// 2. Simple Frustum Culling in View Space

// Check if the sphere is behind the camera or too far to the sides

// Note: This is a simplified check. A proper implementation checks all planes.

bool isVisible = true;

if (-viewPos.z < -instanceRadius || -viewPos.z > 1000.0) {

isVisible = false;

}

// 3. Degenerate the triangle if culled

if (!isVisible) {

gl_Position = vec4(0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0);

return;

}

// Standard projection

vec3 finalPos = position + instancePosition; // Simplified local offset

gl_Position = projectionMatrix * modelViewMatrix * vec4(finalPos, 1.0);

}

`,

fragmentShader: `

varying vec2 vUv;

void main() {

gl_FragColor = vec4(1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0); // Debug Red

}

`,

// Enable instancing

instancing: true

});This approach allows us to submit a massive draw call containing all meshlets, but the GPU only rasterizes the visible ones. This is similar to techniques discussed in Rust News (w/ WGPU) or C++ native graphics programming, but adapted for the constraints of JavaScript and WebGL.

Section 3: Advanced Techniques—Continuous LOD and Error Metrics

Culling hides what isn't seen, but LOD (Level of Detail) optimizes what is seen. The "Nanite" magic lies in selecting the correct resolution for a meshlet based on how many pixels it occupies on the screen. This ensures that we never render triangles smaller than a pixel.

To achieve this in Three.js, we need a hierarchy of meshlets. A parent meshlet represents a simplified version of its children. We calculate the Screen Space Error (SSE) to determine whether to draw the parent or split it into its children.

Calculating Screen Space Error

This calculation must happen every frame. In a pure WebGL 2 pipeline, this is often done using Transform Feedback or by reading textures, but with the advent of WebGPU (often discussed alongside Deno News and Bun News for next-gen backends), we can use Compute Shaders.

Here is a logic snippet for calculating the error metric, which determines if a cluster provides enough detail:

/**

* Calculates the projected screen size of a bounding sphere.

* Used to determine if a meshlet provides enough detail.

*/

function getProjectedError(boundingSphere, camera, screenHeight) {

// Distance from camera to meshlet center

const distance = camera.position.distanceTo(boundingSphere.center);

// Avoid division by zero

if (distance < 0.001) return Infinity;

// Calculate projected radius in pixels

// fov is in degrees, convert to radians

const fovRad = THREE.MathUtils.degToRad(camera.fov);

const cotHalfFov = 1.0 / Math.tan(fovRad / 2.0);

// Projected size estimation

const projectedRadius = (boundingSphere.radius * screenHeight * cotHalfFov) / (2.0 * distance);

return projectedRadius;

}

// In the render loop

function updateLODs(scene, camera, renderer) {

const thresholdPixels = 4.0; // Target triangle size in pixels

// Iterate through the hierarchy (simplified CPU-side logic)

// In production, this loop moves to a Compute Shader

for (const node of hierarchyNodes) {

const error = getProjectedError(node.boundingSphere, camera, renderer.domElement.height);

if (error < thresholdPixels) {

// Error is low enough, render this cluster

node.isVisible = true;

node.children.forEach(c => c.isVisible = false);

} else {

// Not enough detail, traverse to children

node.isVisible = false;

node.children.forEach(c => c.isVisible = true);

}

}

}By integrating this logic, developers working with Svelte News or SolidJS News ecosystems can build 3D components that automatically adjust their weight based on the user's device capabilities and screen size.

Section 4: WebGPU and the Future of Rendering

While WebGL 2.0 allows for some of these optimizations, the true potential of virtualized geometry is unlocked by WebGPU. WebGPU gives us access to Compute Shaders, which can handle the LOD selection and culling entirely on the GPU, freeing the JavaScript main thread for application logic (crucial for frameworks like Remix News or Nuxt.js News where hydration and state take priority).

Three.js is rapidly adopting WebGPU through its WebGPURenderer and TSL (Three Shading Language). Here is how a compute setup looks for managing geometry visibility:

import {

fn, float, vec3, storage, instanceIndex

} from 'three/tsl';

// Define storage buffers for meshlet data

const meshletPositions = storage( meshletPositionBuffer, 'vec3', 'meshletPositions' );

const visibilityBuffer = storage( visibilityArray, 'int', 'visibility' );

// TSL Compute Function

const computeVisibility = fn( () => {

// Get current meshlet index

const index = instanceIndex;

// Retrieve position

const pos = meshletPositions.element( index );

// Perform culling logic (simplified)

// In TSL, we would access camera uniforms here

const isVisible = float(1.0); // Placeholder for frustum check

// Write to visibility buffer

visibilityBuffer.element( index ).assign( isVisible );

} );

// Setup the compute node

const computeNode = computeVisibility().compute( count );

renderer.compute( computeNode );This approach aligns with the modernization seen in Vite News and Turbopack News—moving processing closer to the metal and optimizing the build and runtime pipeline.

Best Practices and Optimization

Implementing virtualized geometry is complex. Here are critical best practices to ensure your application remains performant across devices, from high-end desktops to mobile phones running Ionic News or Capacitor News apps.

1. Data Compression

Streaming millions of triangles requires efficient data formats. Use Draco or Meshopt compression. Tools discussed in Webpack News and Rollup News can be configured to optimize these assets during the build process. Uncompressed geometry will bottleneck your network bandwidth before the GPU even gets a chance to render it.

2. Memory Management

Virtualized geometry is memory hungry. You must implement a Least Recently Used (LRU) cache to unload meshlets that haven't been seen recently. This is similar to how TanStack Query (often featured in React News) manages server state, but applied to VRAM.

3. Fallback Strategies

Not all devices support WebGPU or even high-performance WebGL 2 extensions. Always implement a fallback strategy. If the virtualized system fails, revert to standard THREE.LOD or a simplified base mesh. This ensures compatibility for users on older browsers, a concern often highlighted in jQuery News (legacy maintenance) and Polyfill discussions.

4. Tooling Integration

Don't build your assets at runtime. Create a pipeline using Node.js News tools or Deno News scripts to preprocess your `.obj` or `.glb` files into meshlet streams. Pre-baking the bounding spheres and hierarchy data saves valuable milliseconds at startup.

Conclusion

The implementation of virtualized geometry in Three.js marks a turning point for the web. We are moving away from the era of low-poly assets and baked lighting into an era of dynamic, high-fidelity rendering that rivals native game engines. While the technique draws inspiration from systems like Nanite, adapting it to the web requires a deep understanding of the unique constraints of the browser environment.

Whether you are a developer following Preact News for lightweight interfaces or Playwright News for testing complex applications, the graphical capabilities of the web are becoming a central part of the user experience. By leveraging Meshlets, GPU-driven culling, and the power of WebGPU, we can build worlds that were previously thought impossible in a browser tab.

As tools like Vite, Esbuild, and SWC continue to accelerate our development workflows, and libraries like Three.js continue to abstract the complexities of the GPU, the barrier to entry for high-end graphics is lowering. The future of the 3D web is detailed, fast, and infinitely scalable.